Welcome to H2020 REPAiR online handbook of knowledge transfer.

This handbook provides regional and local policy actors with hands-on guidance and ideas on how to engage in knowledge transfer in a way that helps to avoid the typical pitfalls of learning from foreign best practices. It is based on the H2020 REPAiR project and its unique experience of knowledge transfer between six European Peri-Urban Living Labs (PULLs) in the field of circular economy and resource management. The work of the PULLs was supported by the Geodesign Decision Support Environment, the core product of REPAiR, which provided a platform for discussion on objectives for circular economy transition for each of the case study regions, identification of stakeholders and areas for spatial implementation of eco-innovative solutions and strategies. Therefore, the handbook is most useful for regional or urban practitioners interested in transferring strategies and solutions in this particular policy field; however, it can also provide valuable methodological lessons and insights for knowledge transfer in territorially-focused policies promoting sustainable urban and regional development.

The aim of this handbook is to provide policy-makers as well as other regional and urban practitioners and policy actors with accessible step-by-step guidance and inspiration on inter-regional or inter-city knowledge transfer in the field of circular economy and resource management.

1. Introduction

Learning from policies and solutions implemented abroad or exchange of the so-called best practices is a common-place phenomenon in across virtually all fields of public policy. In an increasingly globalised and interconnected world, seeking solutions to local problems abroad and learning from foreign experiences by local, regional or national government to improve domestic policies has become the norm. Policy-makers and other policy actors operating at national, regional, or local levels routinely seek to learn from the successful policies, strategies or solutions implemented abroad to address domestic policy failures or seek inspiration for new initiatives. Despite its popularity, as underscored in rich academic literature on this topic (see e.g. Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000; Rose, 1991) and proliferation of repositories of good practice, and programmes facilitating inter-regional or inter-city knowledge exchanges, learning from abroad is a process riddled with uncertainty about the fit of a foreign solution in the recipient context. This, in turn, entails the risk of transfer of solutions which are ill-suited and may thus lead to disappointing outcomes. The uncertainty concerns the ‘transferability of solutions across the vastly differentiate states, regions or cities having different governance systems, administrative cultures, knowledge in use in everyday life, technological advancement, patterns of stakeholders’ involvement and their interests, objectives and focus of policies, geographical features, to the less tangible and socio-cultural aspects. This uncertainty is all the greater in cases where the policies or solutions transferred are relatively new, complex and place-specific, as is the case for circular economy solutions and, in particular those that are innovative and embedded in the specific territorial strategies and local geographies of material flows. However, knowledge transfer definitely remains a worthwhile exercise. In the process of devising solutions to complex problems affecting a particular territory, foreign experience can provide a useful source of inspiration, cautionary tales, ideas, understandings or concrete measures, which can enrich the spectrum of possibilities and knowledge pool available to decision-makers.

This handbook provides regional and local policy actors with hands-on guidance and ideas on how to engage in knowledge transfer in a way that helps to avoid the typical pitfalls of learning from foreign best practice. It is based on the H2020 REPAiR project and its unique experience of knowledge transfer between six European Peri-Urban Living Labs in the field of circular economy and resource management. Thus, it is most useful for regional or urban practitioners interested in the transfer of strategies and solutions in this particular policy field, however, it can also provide valuable methodological lessons and insights for knowledge transfer in territorially-focused policies promoting sustainable urban and regional development.

The following sections explain the aim and relevance of this handbook (1.1), the theoretical underpinnings (1.2) and background (1.3) to the methodology on which this handbook builds.

1.1 Aim and relevance

The aim of this handbook is thus to provide policy-makers as well as other regional and urban practitioners and policy actors with accessible step-by-step guidance and inspiration on inter-regional or inter-city knowledge transfer in the field of circular economy and resource management.

This handbook aims at helping practitioners to go beyond mere ‘learning from abroad’, by proposing a methodology that supports the emergence of new knowledge through collaborative relations among stakeholders from different regions and cities. In other words, the goal is to draw attention and provide the means to go beyond a simple transposition of a practice developed in ‘place A’ to ‘place B’ and engage in co-creation of knowledge in international stakeholder networks, collaborating as part of networks of living laboratories, project consortia or other cross-regional or cross-city collaborative projects. The advantage of such a jointly created knowledge is that it is based on shared understandings and thus more readily transferable and applicable to various contexts.

While focusing on knowledge transfer on the circular economy, the usefulness of this handbook goes beyond this topic. In fact, the methodology proposed here, the barriers observed, as well as the practical guidance and tips included, are all of relevance for transferring knowledge in other policies with a territorial focus, from regional development policies, regional or urban sustainability or climate change policies, to urban planning. The handbook is also particularly relevant for urban and regional practitioners involved in international research, investment or knowledge exchange projects, bringing together consortia of stakeholders from different regions and cities collaborating on a territorially-focused policy over a time period allowing for iterative multi- or bi-lateral meetings during which knowledge transfer can be facilitated. Examples of such projects include especially Interreg and Urbact projects, the very purpose of which being interregional or intercity knowledge exchange, but also projects implemented as part of Horizon Europe programme or ESPON funding schemes.

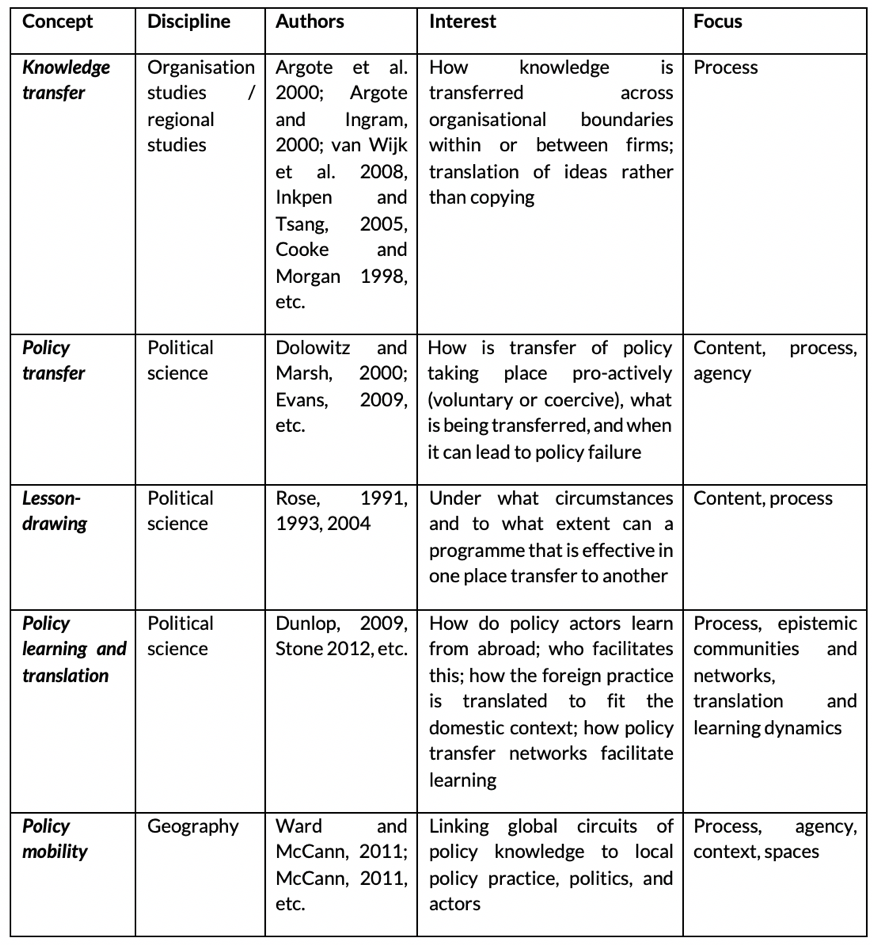

1.2 Theoretical underpinnings

What is knowledge transfer?

Knowledge transfer is a term that originates from organisation studies, where it was used to study how knowledge ‘travels’ between firms and contributes to innovation processes (Argote and Ingram, 2000; Argote, Ingram, Levine, and Moreland, 2000; Inkpen and Tsang, 2005; Simonin, 1999). In other words, knowledge transfer is about transferring and learning innovative solutions through a network of organisations.

In this context, the notion is applied mainly to conceptualise and implement the generation and flow of knowledge (designs, technical solutions, governance arrangements, stakeholder engagement techniques and tactics, policies) related specifically to eco-innovative solutions and strategies for the development of circular economy between regions and cities.

Policy transfer, lesson-drawing and policy translation

‘Policy transfer’ (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996, 2000; Evans, 2004) and ‘lesson-drawing’ (Rose, 1991, 1993, 2004), concepts closely related to that of knowledge transfer, put an emphasis on the process of transfer itself and on its content. Dolowitz and Marsh defined policy transfer as ‘knowledge about how policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in one political setting (past or present) are used in the development of policies, administrative arrangements, institutions and ideas in another political setting’ (Dolowitz and Marsh, 2000, p. 5). The policy transfer literature considers the movement of policies from one context to another as either voluntary or coercive, but always proactive process, taking place mainly among politicians and state bureaucrats, but also policy entrepreneurs including think-tanks, knowledge institutions, experts, pressure groups, global financial or corporate players, or international or supranational organisations (Stone, 2000). Thus, the emphasis is also on the agency and not only on who is involved but also on why.

Pitfalls of knowledge transfer

Transferring knowledge on policy from abroad, while widely used, remains a process that is risky and riddled with uncertainty. This was recognised by Dolowitz and Marsh, who considered the conditions under which policy transfer could result in policy failure in the recipient country. This may happen in cases where the transfer is uniform (‘one size fits all’, without adaptation to local context), incomplete (only parts of a policy are transferred) or inappropriate (not suitable for the recipient context due to the lack of structural conditions, knowledge or resources, for instance). In a similar vein, Evans (2009) conceptualised the potential obstacles for this process. First, he distinguished ‘cognitive’ obstacles in the decision-making phase that could stem from limited search for foreign solutions, cultural assimilation through commensurable problem recognition and definition, limiting the options for learning from abroad, or the sheer complexity involved in the process of transfer. Second, he identified ‘environmental’ obstacles which affect the process of transfer itself. Here, the possible obstacles include ineffective strategies to mobilise support for the transfer; the lack of robust transfer networks; structural constraints related to the recipient context (socio-economic, political or institutional); or, finally, the more prosaic technical implementation problems, stemming from lack of resources or technical capacity. Third, Evans also stressed ‘public opinion’ as another potential obstacle for policy transfer. Here opposition to transfer of foreign policies may come from elite opinion (economic, political, bureaucratic), the media or the constituency groups (voters).

Learning from glossy ‘best practice’ examples is nowadays commonplace and widely promoted by international actors, from international organisations like the European Union, the World Bank or the United Nations, to transnational networks of cities. This common facet of knowledge transfer is also not without risk, however (Stead, 2012). While Rose himself recognised that drawing lessons from abroad has to be done with a degree of cautiousness about the suitability of foreign solutions for the recipient context (1991), there is much less recognition of the problems associated with the circulation of best practice and much less research on poor and failed transfer, with the focus being mainly on ‘success stories’ (Stone, 2012; Stead, 2012). In fact, lack of knowledge on how such best practice emerged, what were the other options that were pondered, what was the process that lead to this and what were the possible failures or u-turns in it, creates a risk of misinformed transfer and ultimately failure of the adopted solutions (Stead, 2012). Some policies are so deeply embedded in the peculiar national legal, political, educational or social systems that they cannot be transferred elsewhere (Stone, 2012).

Policy translation and mobility in networked settings

In response to these limitations and caveats related to knowledge transfer, scholars adopted a more critical view and proposed new theoretical lenses to study and guide the process of learning from abroad. For instance, the notion of ‘policy translation’ was put forward (Stone, 2012) as a ‘move away from thinking of knowledge transfer as a form of technology transfer or dissemination, rejecting if only by implication its mechanistic assumptions and its model of linear messaging from A to B’ (Freeman, 2009, p. 429). In the process of translation of a foreign practice to the local ‘language’ hybridisation and learning processes take place. This, in turn, can lead to the emergence of new policy meanings and a significant departure from the ‘original’ imported practice. The possible merit of such translation process is that it can result in ‘a more coherent transfer of ideas, policies and practices’ (Stone, 2012, p. 488).

Research has underscored that cooperation, open communication, and trust between the actors involved are crucial factors supporting effective knowledge transfer (Bellini et al., 2016). It is thus important to create network settings in which collaborative relations, based on trust, can flourish and support knowledge transfer (e.g. Inkpen and Tsang, 2005). In such settings, the informal relations between the organisations for knowledge transfer may be more important than formal interaction channels, communications and structures. This is particularly true in situations where there are significant cultural differences between the actors which can be clarified in informal settings (Ado, Su, and Wanjiru, 2017), allowing for a well-informed process of translation and adaptation of foreign practices to the recipient context.

Policy transfer networks comprising a large variety of actors, as opposed to closed bureaucratic networks, also have the ability to facilitate ‘soft’ aspects of transfer (Evans and Davies, 1999; Stone, 2000, 2004). Soft forms of transfer entail spreading of norms and ideas, concepts and attitudes, which play an important role in shaping the behaviour of actors and the trajectory of policy change while leaving room for adaptation of the content of the transfer to the local specificities and needs.

Finally, geographers interested in this topic observed that ‘global relational mobilities’ occur in international networks through which policies emerge and travel, but also that these networks do not float in a vacuum, but rather are anchored in specific spaces. In fact, these ‘socio-spatial nodes within global circuits of policy knowledge’ (McCann, 2011, p. 111) provide space in which policy knowledge is produced, modified and reinterpreted as it travels across space. These spaces are often cities, but also the less tangible spaces of policy travel, co-presence and learning, such as the spaces of fact-finding trips and study visits or conferences and seminars where policy actors meet and exchange (McCann, 2011, p. 118).

Take-away messages from the literature

In sum, the above brief overview of the literature and theories that informed this handbook was distilled into a set of guiding principles for knowledge transfer. Thus, successful knowledge transfer is facilitated by:

- Developing an in-depth understanding of both ‘sender’ and ‘recipient’ contexts, going beyond learning from sanitised accounts of ‘good practice’ or ‘success stories’ ;

- Paying attention to what aspect of a solution is being transferred and how to ‘translate’ it locally;

- Operationalising transfer activities in an iterative network setting, with opportunities for face-to-face interaction and first-hand experience of the ‘sender’ context;

- Joint reflection with actors from the ‘sender’ and ‘recipient’ contexts on :

- the ‘how’ question: identifying general barriers; critical contextual differences; and channels to ensure transferability of eco-innovative solutions;

- the ‘what’ question: understanding of a solution in its context and identifying which aspects of it are universal and which place-specific;

- The ‘who’ question: engaging research and practice stakeholders from ‘sender’ and ‘recipient regions/cities in a dialogue to facilitate an understanding of how solutions emerge, enact knowledge co-creation and promote strategic translation in the process of transfer.

2. A co-creative knowledge transfer methodology

The methodology for knowledge transfer on which this handbook builds was devised for the purpose of the REPAiR project, albeit with the ambition to offer guidance beyond this project. It is, therefore, worthwhile to briefly introduce the focus of REPAiR (a more detailed introduction to the project can be found here). The project looks at resource management and circular economy through a territorial lens. It focuses on how the design of physical structures (buildings, infrastructures, cities, etc.) and their social and urban metabolisms, including health, economy, well-being and happiness, are affected by material flows and their environmental impacts. The project aims at integrating material flow analyses and lifecycle analyses into spatial models and planning policies. Moreover, it focused on developing eco-innovative solutions and spatial strategies promoting circular economy in close collaboration with stakeholders in six European regions. These are those solutions and strategies that were the object of interregional knowledge transfer in REPAiR.

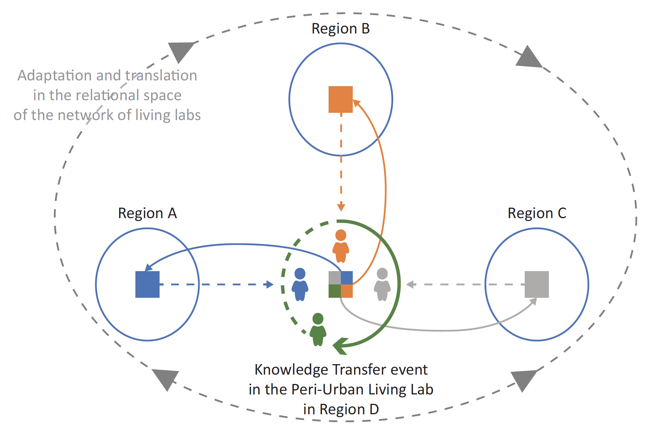

The main platform for knowledge transfer is the network of Living Laboratories (LLs), located in the said six regions. This allows for observing how eco-innovative ideas are co-created and then are travelling among different actors and places with different (disciplinary and socio-cultural) backgrounds and finally, how they are further discussed with local stakeholders in order to adapt them, transform them entirely or partly to make it work in another regional setting.

The network of PULLs is a set of physical and virtual environments, in which public-private-people partnerships experiment with an iterative (co-creation) method to develop innovations (Eco-innovative Solutions/EISs) using an open-source geodesign decision support environment (GDSE) software and responding to the case-specific challenges. The process includes the involvement of end users too. REPAiR implements LLs in six European Peri-Urban Areas: the Peri-Urban Living Labs (PULLs) (see more details on PULLs in D5.1 of REPAiR project).

During PULL workshops, so-called “knowledge transfer events” were organised as a separate workshop dedicated to discussion on transferability of eco-innovative solutions elaborated in other case study areas.

Figure 1 – Co-creation and mobility of EIS in a network of living labs.

Source: Dąbrowski et al., 2019

(Eco-Innovation refers to all forms of innovation – technological and non-technological – that create business opportunities and benefit the environment by preventing or reducing the environmental impact, or by optimising the use of resources…Other than products, if we speak about services, they cannot be seen, tasted, touched, or smelled; a service can be an activity, a performance, or an object; it can be included in a product (D5.1 of REPAiR project).

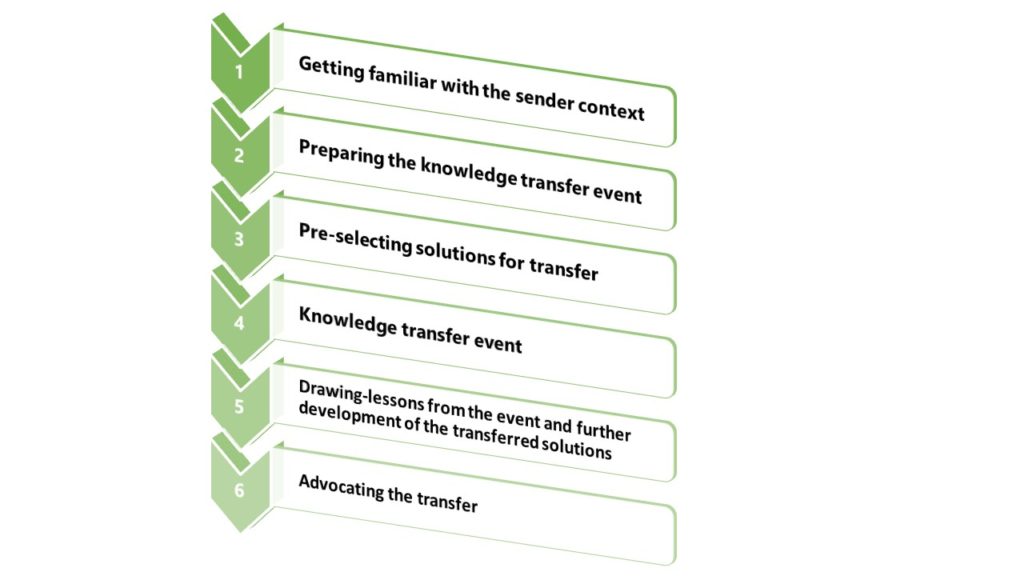

2.1 Outline of the methodology

The methodology described here is the result of the co-contribution of WP5 (organiser of PULLs) leaders, the results of the research in WP3 (processes in the case study areas). The methodology has been tested and refined (based on the feedback) in six PULLs (in Amsterdam, Naples, Ghent, Hamburg, Łódź and Pécs). Based on this experience, we developed a step-by-step methodology as guidance in order to successfully transfer EISs from one place to another. Although this methodology derived from the REPAiR project, the aim of this guideline is to give a clue for reuse the steps in other cases and topics where EISs are targeted to transfer from one place to another. So, as in the methodology can be seen, follow the steps then adapt the methodology to your case.

2.2 Methodology steps

Step 1 – Getting familiar with the sender context

Based on the scientific literature and our research experience, there are several types of barriers that hamper the transfer of EISs from one place to another. The different types of barriers can hamper the transfer in different ways. For preparing (and for understanding the role of obstacles in EIS transfer), we summarised the most crucial barriers in the following Table.

Table 2 – Barriers to knowledge transfer.

| Barrier | How it hinders transferability of EIS – (examples) |

| Language | Most of the EISs are in English. Without knowing the language properly it is difficult to understand what to transfer. |

| Disciplinary background | Difficult communication between transfer actors with social science and engineering or design background. |

| Geography (of metabolic flows) | The difference between geographical circumstances affects metabolic flows and applicability of solutions (e.g. dense water lanes in one place, mountainous in another place need different solutions in waste collection) |

| Socio-cultural | Differences in waste sensitivity, environmental culture, and other socio-cultural specificities may make stakeholders non-receptive to some solutions in one region, and there is a need for more promotion |

| Socio-economic differences | A higher level of economic development tends to be related to more advanced environmental culture; pragmatically, more wealthy regions are able to dedicate more resources to innovation in circularity; on the other hand, poorer regions have to face other challenges (e.g. waste burning, instead of separate collection) |

| Other socio-political phenomena | Public opposition to the transfer of foreign policies may block transfer (e.g. in a Eurosceptic region it is harder to implement an EU directive) |

| Legal aspects | A discrepancy in legislation between the two contexts may prevent implementation of an imported solution |

| Governance and decision-making | Divergent governance arrangements may undermine the implementation of an imported solution (e.g. excessive centralisation does not allow local decision, for instance in selling separately collected plastic locally, in case the secondary raw material trade is centralised) |

| Technological aspects | When the recipient region is at a lower stage of development of circular technologies transfer is hindered |

The following video can give more explanations about the role of the barriers:

It is essential – as a first step – to get familiar with the sender region/case area. To do so, in the REPAiR project, we made a very detailed document about the CE related processes in the case study regions (see more details in the D3.3, 3.5, 3.6, 3.7 process models of the REPAiR project).

If you do not have the opportunity to find a detailed description of a given region, you might pose – in this initially step – the following questions in order to get familiar with the given area:

1) In which language is the EIS written? Do the stakeholders understand this language?

2) What kind of expertise is needed for understanding the sender case? Do your stakeholders have this knowledge?

3) Similarities in geography.

- Are the following aspects similar?: 1. relief; 2. surface waters; (physical morphology, hydrography.) It is easy to use Google Maps or Google Earth for that purpose;

- Where and what types are the most important/challenging wastescapes in the sender and recipient region. (Ask this information from the sender region stakeholders; check the sender region’s physical plan, city development plan, or development strategy);

- What are the main properties of the built environment in the sender region? (Check the physical plan of the region/city and/or Google Map);

- How is the land use in the sender region? You might use the EU’s online CORINE webmap.

(You can also check whether the sending region is undergoing serious change in land use or not, following the high-resolution maps of this article)

4) What are the levels of waste sensitivity in the sender region?

Check the relevant data of this Eurobarometer survey.

(Note: a more complex index was created in the REPAiR project based on the database of this survey (in D3.8, see the details there as well). In a case you have the opportunity, you can make the same index and its visualisation to your region.

5) Reveal the socio-economic aspects of the sender region.

(Note: For that, the best information can be gained from local development plans that includes basic data. Also you can check the national statistical offices of the sender region.)

You can find the most comprehensive data on the EU Eurostat website.

The following data can be useful: population, demography, economy, science and technology, environment and energy, labour, poverty. Additionally, you can check here further relevant information.

6) State of the technology and innovation.

Different countries, regions are in a different stage in technology and innovation. It partly depends on the state of economic performance of a region and partly on the technological traditions (e.g. A special technological tradition in The Netherlands is to incinerate MSW (municipal solid waste) for generating electricity, while in the Pécs region (Hungary) from combustible waste RDF (refuse-derived fuel) or SRF (solid recovered fuel) is created for cement factories for co-firing purposes.

Another indication about the level of the innovation level is mapped here. This database allows you to compare the different NUTS2 regions and have a look at on the temporal trends.

7) The quality of government in the sender and recipient regions.

Here you can compare 4 aspects of governance between the two regions you are dealing with in the EIS transfer.

Once you are getting familiar with the sending region, please make notes and evaluate how similar your region is to the sending region, revisiting the aspects above .

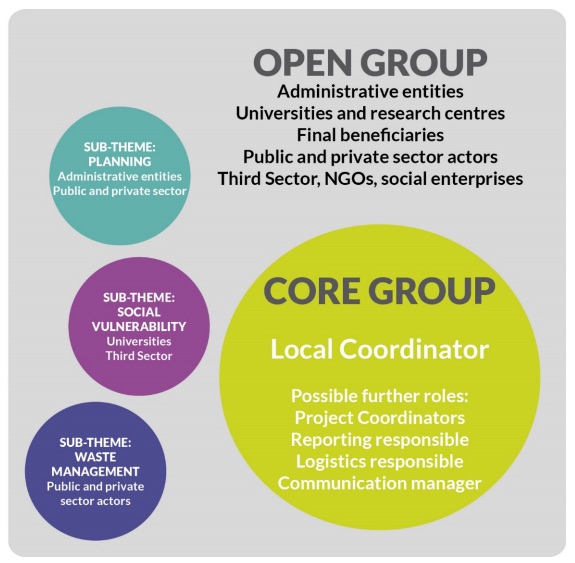

Step 2 – Preparing the knowledge transfer event

First of all, it is recommended that the knowledge transfer event will be a part of a Living Laboratory (such as in the REPAiR project), or another collaborative network (a good example would be the workshop activities bringing together stakeholders and project partners in Interreg or Urbact projects). Such a setting should allow for holding a series of participatory workshops. It allows participants to get to know the challenges and targets of their own case study area (e.g. how decisions are made; what are the most important case-specific legislations; where are the hotspots of the challenges etc.).

The preparatory sub-steps are the same as for the organisation of the living labs. Therefore, here we only indicate these sub-steps, referring to the Handbook of organising (PU)LLs (developed as part of the REPAiR project).

1) Set a location (more detail here).

2) Define the internal role of organisers.

Additionally, do consider:

– inviting a person from the EIS sender region (who can present the EIS and answer the questions raised by the local stakeholders);

– inviting interpreter(s) who can translate between the ‘sender’ and ‘recipient’ members — in case the two part do not speak each other’s language.

3) Engage further with stakeholders.

This document provides some useful tips for engaging stakeholders.

4) Invite stakeholders to the Knowledge Transfer event (KT event), describing shortly what it is about.

Once you have the list of potential participants, and there are more than five, split them up into groups. Based on your engagement and previous knowledge on stakeholders, make mixed groups, ensuring that each group includes the possibly biggest variables of the stakeholders regarding their background discipline and expertise.

Step 3 – Pre-selecting solutions for the transfer

After you get to know the circumstances of both the sender and recipient case areas, you might have a clue on what kind of solutions can be useful for the recipient decision-makers. It is crucial, because:

- it ensures that an EIS is selected that suits the best to the recipient’s technological and innovation level;

- it is easier to get to choose a solution to adapt from a preselected list as nowadays dozen of solutions available (here and many other sites on the internet) and looking through them is time-consuming, therefore counterproductive (lost the focus) for stakeholders and decision-makers.

- How to pre-select solutions for transfer?

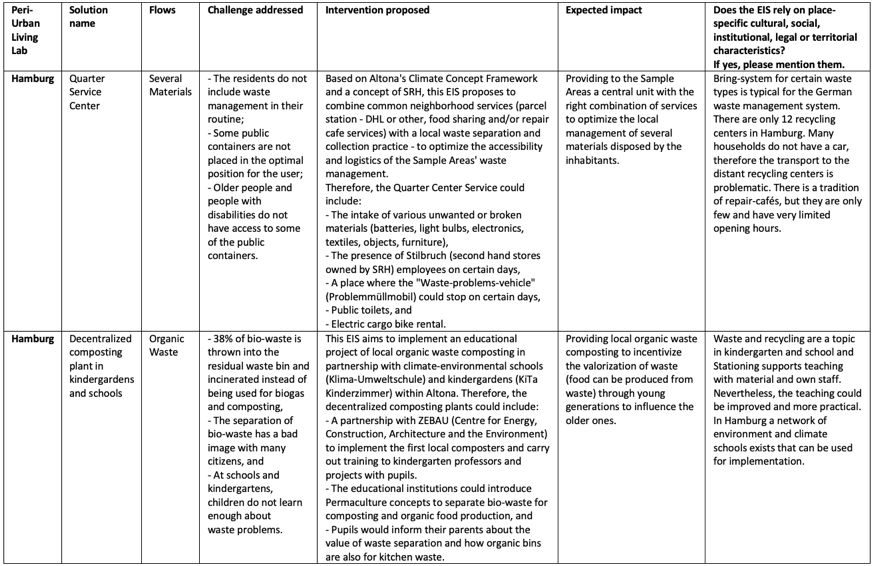

It can be worthwhile to prepare a table for the purpose of preselection of solutions, containing short description and basic information on the solutions to be transferred. It could be helpful for the transfer participants to quickly scan the pool of solutions available for transfer. The figure below shows, as an example, an excerpt from such a table.

Depending on your time available (would not be more than two-hour-long session), you have to choose no more than 4 EIS for the workshop. The less the better this is and you have time for further thinking on the adaptation of solution(s).

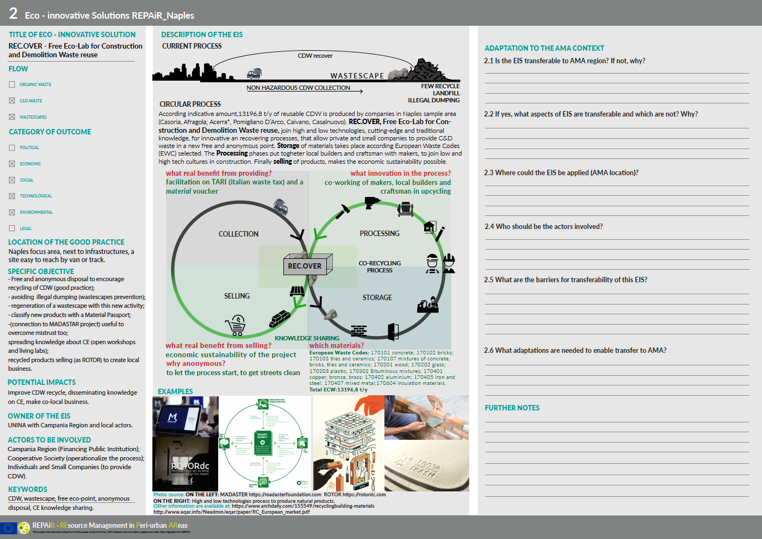

After preselecting the solution(s), prepare a so-called Knowledge Transfer sheet (KT sheet). This sheet helps:

- your stakeholders to remember to the key issues of the presented EIS and to go through the questions of adaptability of the given solution;

- you to go further to the step No.5.

The sheet can be redesigned to suit the needs of your project or situation, but it is essential that it offers space for elaborating on the properties of the solution, the flows and stakeholders involved and presenting some visual material explaining and contextualising the solution. This basic description on the sheet then provides support for discussion between the stakeholders from sender and recipient places during a knowledge transfer event. This is facilitated by the questions guiding the discussion on: transferability of the solution; possible location for its implementation in the recipient place; barriers for transfer and adaptations needed; and stakeholders to be involved in the implementation of the solution transferred.

Step 4 – Knowledge transfer event

Once you arrived here, you have invited stakeholders and you have chosen no more than four EISs for discussion.

[It is always a debate how many EISs can be useful. Stakeholders would like to know as much as possible new solutions. On the other hand, there is a limit to deeply discuss major amount of solutions in one time, especially if there are similar aspects in the solutions that can lead to boredom. Our experience is that four, carefully selected solutions, are enough for a successful knowledge transfer event during a workshop series and/or Living Laboratory]

In case there are many people present at the workshop, you are advised to create two or more working groups. The more working groups you have, the more circumstances are taken into account for a more successful adaption.

It is advised that one working group does not consist of more than three or four stakeholders, plus a coordinator (who also takes notes, unless there is an additional notetaker), the EIS sender – who can present the EIS adequate and answer the questions during the workshop, and translator(s), in case the ‘sender’ and the ‘recipient’ do not speak each other’s language.

[Tip: It is worth to split-up the stakeholders well-before the event, and at the end of the introductory part of the event you can show/tell who should go into which group. Hence, you can ensure that each group can have a variety of experts with different interdisciplinary backgrounds.]

Starting the group work, after a short introduction, the coordinator asks the EIS sender participant to shortly present the EIS.

[Tip: Using a digital slideshow and several pictures as figures can help the local/recipient stakeholders to grasp better the EIS].

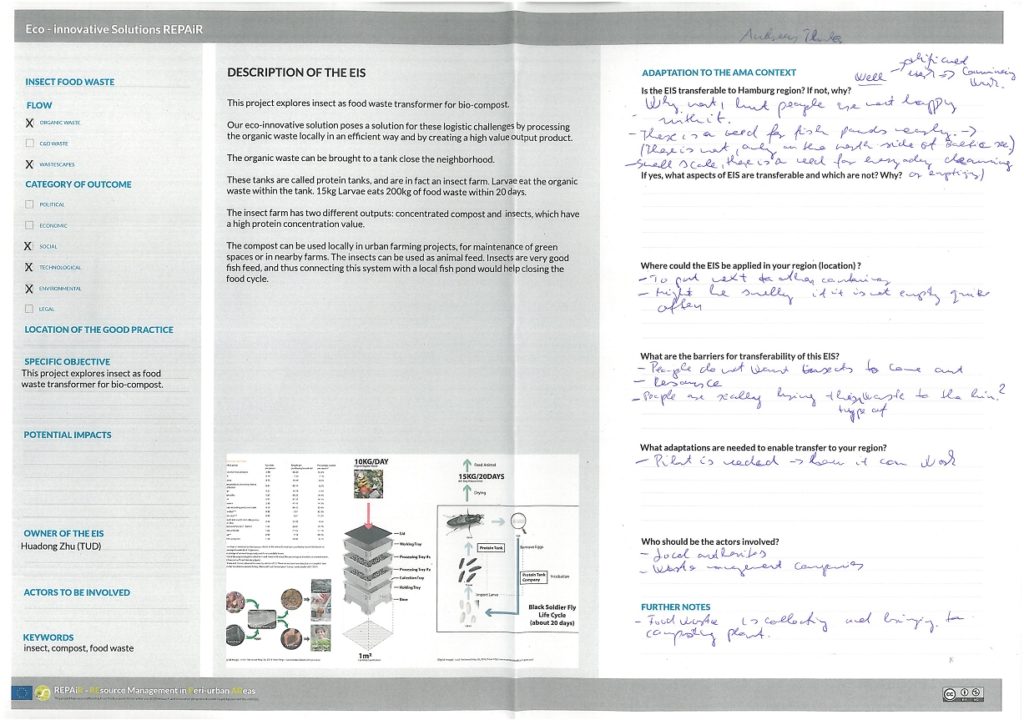

After the presentation, the coordinator has to initiate a discussion about the adaptability of EIS. For that, the easiest way is to give the stakeholders the so called “KT sheet” and to ask them to fill in the questions.

[Tip: In case there is a need to warm-up the conversation, the coordinator can provide coffee and tea; he/she should ask the EIS sender to tell some more words and/or ask stakeholders one-by-one about the adaptability (first question)].

For a more productive event (and for the success of the next step), the coordinator can ask one of the stakeholders at the beginning to write down the answers and fill in the KT event sheet (like shown in the figure below).

Give about 25-30 minutes for one EIS, then start to discuss another EIS. During a KT Event, for the sake of maintaining focus and avoiding the fatigue of the participants, it is suggested not to include more than four EISs in the discussion.

Once the group is done working, the group coordinators give a few-minutes summary of the main findings of the groups. That helps to reveal and to see the differences of the groups more clearly; hence it can shed light on additional aspects of the adaptation of the solutions needed.

[Tip: Make sure to take notes during the session. If it is doable, make video recording as well]

Step 5 – Drawing-lessons from the event and further development of the transferred solutions

The most crucial further step is to summarise what you have learned and transfer it to your context into practice. To do so, you have to revisit your materials and notes. For further developing the solution:

- Collect the barriers from different working groups. Group the barriers – preferably – by the “category of outcome” in the KT sheet (in other words, based on the widely used PESTEL model referring to political, economic, social, technical, environmental and legal factors affecting a given process).

- Assess the degree of transferability of solutions (make a ranking, too);

- Investigate how the solutions changed as they ‘travelled’. List what should be modified and how;

- List who should be the actors involved – Import the list from the KT sheet and add new actors if necessary;

- In case there are questions regarding the adaptability, do not hesitate to further discuss this with your stakeholders and experts individually.

After that, make your further developed documentation on your transferable EIS, similar to the original EIS, making sure you cover the following corner-stones:

- the current process;

- the proposed process;

- the evaluation model (where you can evaluate the impact of the changes on the environment, society and economy);

- possible location within your case area.

In case you use external sources for your solutions, you have to provide full references to these sources, in footnotes or a separate references section of the document (an example can be found here).

Step 6 – Advocating the transfer

In order to achieve a real adaptation of a solution, you have to convince actors (who should be involved) and (a) decision-maker(s) to make the decision to adapt the solution. The best scenario is that during the Living Lab, adequate decision-maker(s) are participating. Although, in most cases, this is not the situation. Hence, you have to inform and convince them to make the adaptation work.

To do so, make a synopsis of the above findings including figures, pictures out of the original EIS. Decision-makers tend to be busy people, however, while the EISs tend to be complex. But still, you have to transfer all the necessary information to them. Hence, your synopsis has to be concise, readable, accurate. Just like a policy recommendation.

3. Example of knowledge transfer based on the methodology

The following video offers some tips on adapting a solution to the ‘recipient’ region context:

Having presented the methodology, let’s look into an example of how it was applied. We use here the example of transfer of knowledge between two PULLs as part of the REPAiR project, located in Amsterdam Metropolitan Area and in the Metropolitan Area of Naples.

3.1 Transfer of knowledge between Peri-Urban Living Labs in Naples and Amsterdam

Both PULLs focused on the exploration of material flows and the spatial conditions to develop eco-innovative solutions to promote the circular economy in each of the regions. In particular, special attention was paid to the transformation of the spatial structures for which the solutions were developed, including the regeneration of the so-called wastescapes, that is underused, abandoned, often polluted wasted landscapes, such as brownfields or infrastructure buffer zones (see Amenta & van Timmeren, 2018). The solutions concerned the flows of construction and demolition waste (C&DW) as well as flows of organic waste.

Knowledge transfer events were held first in Amsterdam and then, a couple of months later in Naples. For each of them, stakeholders from the other region were invited to take part and brought with them a selection of EISs from their region. This selection was based on an earlier choice of the most suitable solutions for transfer from among wider catalogues of solutions elaborated in Amsterdam and Naples. The pre-selection was made by the stakeholders from each of the regions prior to the knowledge transfer events, leaving time to the stakeholders from the ‘sender’ regions to prepare summaries of the solutions chosen.

To keep this account concise, we focus on an example of just one solution for the transformation of wastescapes: “RECALL: REmediation by Cultivating Areas in Living Landscapes” (for a more detailed account of the knowledge transfer process between Amsterdam and Naples PULLs see this paper). The solution aimed proposed bio-based remediation of polluted soil in post-industrial land to enable its eventual reuse. This is done using hemp and other local crops. The original solution was supposed to address the huge problem of polluted land in the Naples region, often due to illegal dumping of hazardous waste. The solution builds on local traditions of manufacturing products from hemp fibres (such as cloth, string) and the high capacity of this crop to remove heavy metal pollutants from soil in a relatively short period. The solution can bring back polluted wastescapes to ‘productive’ life, while providing opportunities for revitalising a traditional local industry.

For this example, we will cover three issues: (1) barriers for transfer; (2) the degree of transferability; and (3) adaptations that were needed to make the solution work in the Amsterdam region.

Barriers

The participants of the knowledge transfer event in Amsterdam indicated that the main barriers were geographical and socio-economic. They related this mainly to the scarcity of land in the Amsterdam area and surging demand for land for residential and commercial development projects. While not facing a similar waste emergency and magnitude of soil pollution problem as Naples, the Amsterdam region has a substantial amount of polluted wastescapes, especially in the area of the Port of Amsterdam, making the transfer of this solution interesting. However, both said shortage and a high demand for land for development make soil bioremediation with hemp or other crops a less viable option for Amsterdam, unless the solution would be connected to other metabolic flows (for instance construction and demolition materials), thereby widening the appeal of the solution in the eyes of the stakeholders. In fact, housing development or expansion of Schiphol airport are such burning concerns that instead of lengthy hemp-based remediation, the preferred (more economically viable) option in the eyes of planners and/or developers would likely be to simply scrape off a layer of polluted land and dump it elsewhere.

Transferability

That said, the stakeholders involved generally saw this practice as highly transferable, given the soil remediation needs in the areas of urban expansion for Amsterdam. Also traditions of manufacturing products from hemp fibres are present in Amsterdam and could be tapped into, while the said barriers were deemed surmountable with adaptations to connect the solution to the construction materials flow. This connection to the construction and demolition waste flow could considerably increase the attractiveness of this solution by connecting it to the growing circular construction sector in the Amsterdam region.

Adaptations

Given the above barriers and potential for synergies regarding construction and demolition waste flows, the solution was considerably altered to fit the Amsterdam context. Therefore, the transferred solution departed substantially from the original one. The following adaptations were proposed:

- Expanding the metabolic flows focus to include manufacturing of hemp-based construction materials (such as hempcrete or mycelium blocks). This adaptation reflected the high importance of construction and demolition waste flow in the Amsterdam region as well as the growing demand for (circular) construction materials in the wake of the construction boom and the ongoing expansion of the Amsterdam’s urban tissue.

- Broadening the approaches to remediation of soil, depending on the demand for land in a particular area. Experts proposed that in areas with high pressure on land needed for imminent development, polluted soil layer could be scraped off and transported to a wastescape in a place where development is not imminent, allowing for nature-based remediation, preparing the land for later development.

- Adapting the selection of crops to be used for remediation to the pollution type in a given area.

- Broadening the range of stakeholders involved to include producers of construction materials, builders and developers, as well as grondbanken (soil banks – organisations dealing with assessment and classification of batches of land based on environmental quality and with the logistics of soil flows to and from soil depots).

- Combining hemp-based soil remediation with recreation activities or solar energy production, where possible, which could further broaden the appeal of the solution and attract the support of renewable energy stakeholders.

4. Tips for successful knowledge transfer

Building on the above methodology, experience from knowledge transfer between six European regions in the REPAiR project and advice from the circular economy stakeholders participating in this project, we can draw ten practical tips for a successful knowledge transfer:

- Make an effort to understand well the sender context;

- Be sure you speak the language of the place of origin of the solution (or make sure to have an interpreter with you);

- Visit the sites where the solutions originate from;

- Do talk face-to-face to the people who designed the solutions – they can best explain how it really worked and what it took to make it happen;

- Don’t assume you can simply take a solution from elsewhere and apply it at home – adaptation is a must;

- There is (almost) always something you can learn from a foreign solution, even if it is a mere inspiration sparking ideas for development of own solutions;

- Transfer works best in networks and through longer-term relationships between the stakeholders from the sender and recipient places in which knowledge is shared and co-created;

- Make sure you have the right expertise represented at the table when discussing knowledge transfer;

- Be open to new ideas of the practitioners from other regions and prepared for your ‘ways of doing things’ being challenged;

- Don’t assume that since your region is lagging on the transition towards a circular economy, you cannot learn from the leading regions – ‘leapfrogging’ from improvements to waste management system towards more circular processes is a viable option, if not a necessity.

Apply them and let us know if they worked for you.

If a list of ten tips is not enough, or you wish to hear some of them first-hand, this video offers some further advice and inspiration from the REPAiR’s circular economy stakeholders:

5. Catalogue of eco-innovative solutions for promoting circular economy in cities and regions

Following this link, Eco-Innovative Solutions give you a baseline position to start to transfer these ideas into your region. These solutions are elaborated as part of the REPAiR research project, and are based on literature research, student work and workshops of Peri-Urban Living Laboratories of REPAiR project (i.e., PULL workshops). You can use them under the terms of Creative Commons.

6. References

Ado, A., Su, Z., and Wanjiru, R. (2017). Journal of International Management Learning and Knowledge Transfer in Africa-China JVs : Interplay between Informalities, Culture, and Social Capital. Journal of International Management, 23(2), 166–179.

Amenta, L. and van Timmeren, A. (2018). Beyond Wastescapes: Towards Circular Landscapes. Addressing the Spatial Dimension of Circularity through the Regeneration of Wastescapes. Sustainability, 10(12), 4740. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124740

Argote, L., and Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for Competitive Advantage in Firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150–169.

Argote, L., Ingram, P., Levine, J. M., and Moreland, R. L. (2000). Knowledge Transfer in Organizations: Learning from the Experience of Others. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 1–8.

Dąbrowski, M., Varjú, V., & Amenta, L. (2019). Transferring circular economy solutions across differentiated territories: Understanding and overcoming the barriers for knowledge transfer. Urban Planning, 4(3), 52-62. DOI: 10.17645/up.v4i3.2162

Bellini, A., Aarseth, W., and Hosseini, A. (2016). Effective Knowledge Transfer in Successful Partnering Projects. Energy Procedia, 96(1876), 218–228.

Dolowitz, D., and Marsh, D. (1996). Who Learns What from Whom: a Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Political Studies, 44(2), 343–357.

Dolowitz, D. P., and Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23.

Freeman, R. (2009). What is’ translation’? Evidence and Policy: a Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 5(4), 429–447.

Evans, M. (2004). Policy transfer in global perspective. London: Routledge.

Evans, M. (2009). Policy transfer in critical perspective. Policy Studies, 30(3), 243–268.

Inkpen, A. C., and Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social Capital, Networks, and Knowledge Transfer. Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 146–165.

Evans, M., and Davies, J. (1999). Understanding policy transfer: A Multi‐level, multi‐disciplinary perspective. Public administration, 77(2), pp. 361–385.

McCann, E. (2011). Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: Toward a research agenda. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 101(1), 107–130.

REPAiR (2018) REsource Management in Peri-urban AReas: Going Beyond Urban Metabolism: Deliverable 7.1 – Theoretical model of knowledge transfer. Delft: Delft University of Technology. https://h2020repair.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Deliverable-7.1-Theoretical-model-of-knowledge-transfer.pdf

Rose, R. (1991). What is Lesson-Drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 3–30.

Rose, R. (1993). Lesson Drawing in Public Policy: A Guide to Learning Across Time and Space. Chatham: Chatham House.

Rose, R. (2004). Learning from comparative public policy: A practical guide. London: Routledge.

Simonin, B. L. (1999). Ambiguity and the process of knowledge transfer in strategic alliances. Strategic management journal, pp. 595–623.

Stead, D. (2012). Best Practices and Policy Transfer in Spatial Planning. Planning Practice and Research, 27(1), pp. 103–116.

Stone, D. (2000). Non‐governmental policy transfer: the strategies of independent policy institutes. Governance, 13(1), pp. 45–70.

Stone, D. (2004). Transfer agents and global networks in the “transnationalization”of policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(3), 545–566.

Stone, D. (2012). Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Studies, 33(6), 483–499.